Introduction: A Complex Educational Relationship

India’s relationship with the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) resembles that awkward dance at a party – a brief appearance followed by a hasty retreat to the sidelines. As someone who’s closely followed India’s educational policy developments, I’ve often wondered about this curious absence from what is arguably the world’s most influential educational assessment.

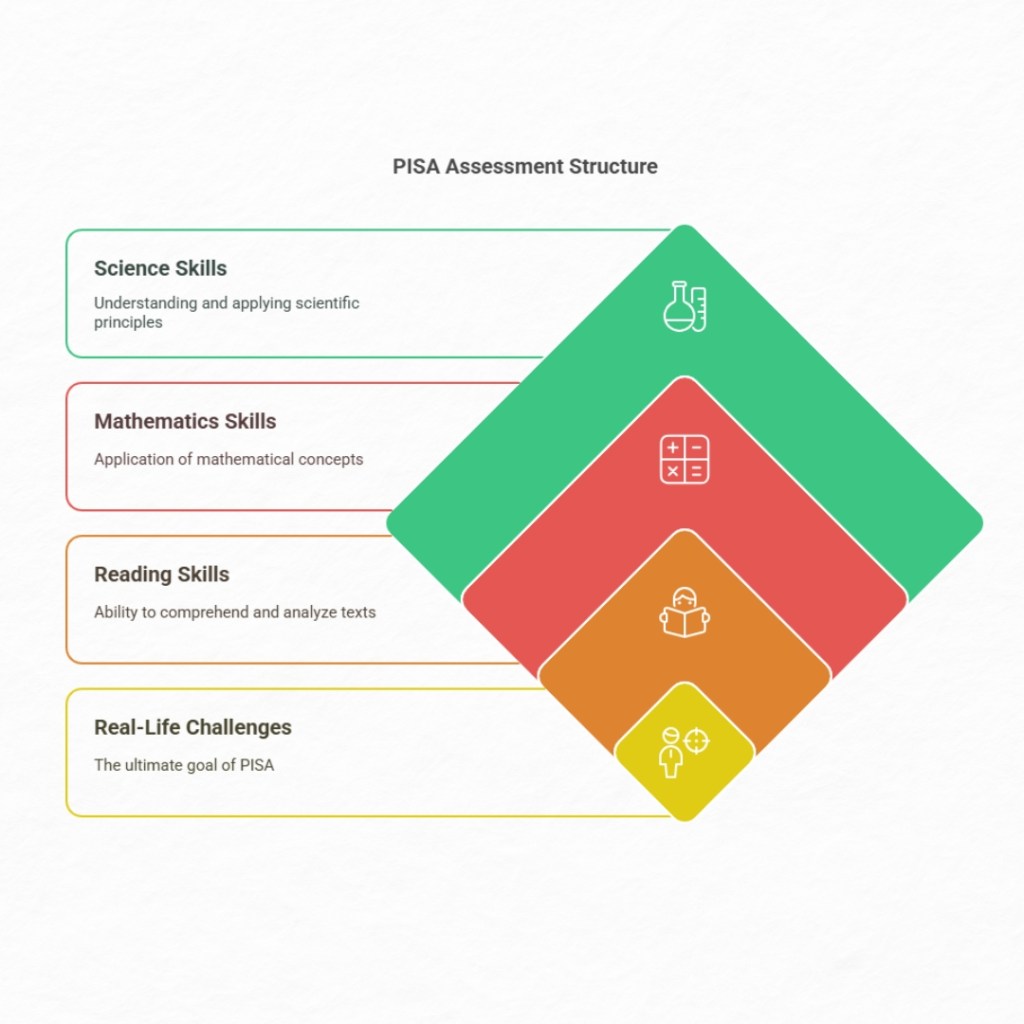

PISA, administered by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), evaluates 15-year-old students in reading, mathematics, and science literacy every three years. While over 80 countries participate in this global educational benchmark, India has largely remained absent from the stage – a significant gap considering it houses the world’s largest youth population.

Table of Contents

The Brief Dance: India’s First and Only PISA Appearance

India’s sole flirtation with PISA came in 2009. Rather than participating nationwide, India was represented by two states – Tamil Nadu and Himachal Pradesh. These weren’t random selections; they were among India’s better-performing states educationally, particularly Tamil Nadu with its robust educational infrastructure.

The results, however, were nothing short of shocking. Both states ranked among the bottom five participants globally, with scores significantly below the OECD average. Tamil Nadu and Himachal Pradesh ranked 72nd and 73rd respectively out of 74 participants, outperforming only Kyrgyzstan.

The Contentious Withdrawal: Official and Unofficial Reasons

Following this disappointing debut, India withdrew from subsequent PISA cycles. The official explanation focused on cultural and contextual misalignments between PISA’s testing approach and India’s educational system. The Ministry of Human Resource Development (now Ministry of Education) cited:

- Language barriers, as PISA questions are primarily designed for Western contexts

- Unfamiliar testing formats that Indian students weren’t accustomed to

- Questions containing references to cultural contexts foreign to Indian students

Unofficially, education policy experts suggest more uncomfortable truths behind the withdrawal:

- The political embarrassment of poor performance

- Reluctance to expose systemic weaknesses in the education system

- Fear that poor rankings would damage India’s emerging global image

The Cultural Mismatch Argument: Valid Point or Convenient Excuse?

The cultural mismatch argument deserves examination. PISA questions often reference skiing, apple farms, and Western urban scenarios – contexts unfamiliar to many Indian students, especially those from rural backgrounds. A question about interpreting a subway map might seem straightforward to a student from Paris but could bewilder a student from rural Bihar who’s never seen a metro system.

However, critics point out that countries like Vietnam, with similar developmental challenges, have performed remarkably well on PISA. China, too, has had impressive results, suggesting that cultural differences alone can’t explain India’s poor performance.

The Deeper Issues: What India’s PISA Absence Reveals

India’s continued absence from PISA speaks volumes about broader challenges in our educational system:

Focus on Rote Learning Over Critical Thinking

The Indian education system traditionally emphasizes memorization over analytical skills. While our students excel at reproducing information, PISA tests application of knowledge to real-world problems – a skill that requires different pedagogical approaches.

Infrastructure and Resource Gaps

The stark reality is that many Indian schools lack basic facilities. According to the Annual Status of Education Report, significant percentages of schools operate without adequate classrooms, functioning toilets, or sufficient teaching staff. How can we expect competitive performance in global assessments when basic learning conditions aren’t met?

Economic and Social Inequality

India’s educational outcomes are deeply intertwined with socioeconomic factors. Students from disadvantaged backgrounds, especially in rural areas, face significant barriers to quality education. PISA might essentially be measuring these socioeconomic disparities rather than the effectiveness of the education system itself.

The Return on the Horizon?

Interestingly, after a decade-long hiatus, India announced plans to participate in PISA 2021 (later postponed to 2022 due to the pandemic). This time, students from Chandigarh, and selected schools from the Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangathan and Navodaya Vidyalaya Samiti were chosen to represent India.

This selection strategy is telling – choosing students from relatively well-resourced central government schools rather than a representative sample of the Indian student population. It suggests that India wants to participate but is still cautious about how it’s represented on the global stage.

What India Loses by Not Participating

By staying away from PISA, India misses out on:

Objective Assessment Benchmarks

PISA provides standardized metrics to measure educational progress against global standards. Without this benchmark, India relies on internal assessments that may not accurately reflect global competitiveness.

Learning from Global Best Practices

PISA participants gain insights into successful educational approaches from around the world. Finland’s consistent top performance, for instance, has led many countries to study and adapt elements of their education system.

Driving Evidence-Based Policy Reform

PISA results often catalyze educational reforms in participating countries. Germany’s “PISA shock” in the early 2000s triggered comprehensive reforms that significantly improved their educational outcomes.

The Way Forward: Embracing Assessment for Growth

As India aspires to become a knowledge superpower, it must eventually face the mirror that PISA holds up. Rather than viewing international assessments as threats, they should be seen as valuable diagnostic tools.

The National Education Policy 2020 shows promising signs of addressing many of the fundamental issues – emphasizing critical thinking, reducing curriculum load, and focusing on foundational learning. These reforms align well with the skills PISA evaluates.

Perhaps the most balanced approach would be to participate in PISA while acknowledging its limitations in the Indian context. By engaging with global assessment frameworks while developing India-specific supplements, we could gain the benefits of international comparison without compromising on cultural relevance.

Conclusion: Beyond the Scores

India’s journey with PISA reflects our complex relationship with global educational standards. While the scores from 2009 were disappointing, they revealed important truths about our education system that deserve attention.

As we move forward, the question shouldn’t be whether India should participate in PISA, but how we can use such assessments to build an education system that equips our youth with the skills they need for the 21st century while honoring our unique cultural and social context.

The true measure of educational success isn’t just about ranking on international assessments – it’s about creating a system that empowers every child with the knowledge, skills, and values to thrive in a rapidly changing world. PISA participation should be seen as one tool in this much larger educational mission.